The Alarming Rise in Self Harming – What is Behind It?

By: Kiran Foster

The 2013 suicide of 15-year old Tallulah Wilson brought the issue of self harming to new heights of public awareness here in the UK. But Tallulah’s tragedy wasn’t the first or the last. What have we learned since then, and are things changing?

What is self-harm?

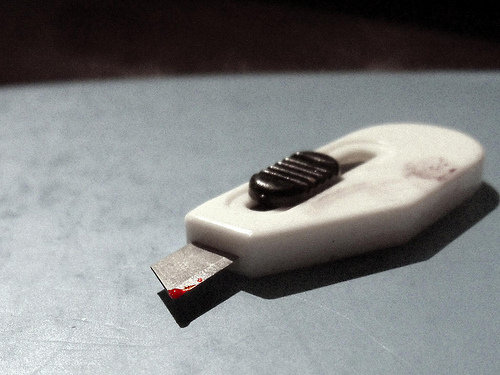

Self-harm is still defined as deliberate injury to one’s body through actions such as cutting, burning, scratching, hair-pulling, poisoning, and drug or alcohol abuse.

(For a detailed overview of self-harm and recommended interventions, read our comprehensive Help Guide to Self-Harm).

It’s a common misunderstanding that the intent of self-harm is to commit suicide, but this is rarely the case. The drive behind self-harm is rather to achieve release or distraction from too much stress, negative thoughts, or situations that seem both intolerable and inescapable. In some cases, harming oneself also serves as self-inflicted punishment for imagined “sins,” such as academic or social failure, or falling short of an unrealistic physical ideal.

Despite it’s prevalence, self-harm is not officially recognised as its own independent disorder here in the UK like it now is in the United States. It is instead generally seen as a symptom of a larger problem.

It is, however, recognised by the the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) that improvement needs to be made around the way self-harm is understood and treated in our country. Their website states that, “Self-harm is poorly understood by many NHS staff. All staff that come into contact with people who self-harm need dedicated training to improve both their understanding of self-harm and the treatment and care they provide. Effective collaboration of all local health organisations will be essential to develop properly integrated services.”

Why are Numbers Still Rising When it Comes to Self-Harm?

By: Chris Chan

One reason for the increase in numbers is that previous studies often focused on young adults aged twelve and up. Since younger children began showing up for hospital treatment of self-harm injuries, researchers have expanded their subject pool to include a lower age bracket.

But while studying a broader pool of people accounts for some increase in the numbers, it doesn’t explain why self-harm is escalating rapidly in groups already being tracked. The alarming rise has caused researchers to re-double their efforts to develop a clearer profile of people at risk.

Two important research overviews published separately in 2014, by the one by the University of Bristol and the one by the National Suicide Research Foundation in Ireland, re-examined several hundred studies for potential risk factors of self-harm.

Both groups of researchers concluded that committing an act of self-harm escalates the likelihood of repetition within a year to over sixteen per cent, and that despite the efforts of mental health professionals this pattern had not changed since studies done back in 2000.

The studies also confirmed that two other established risk factors – past treatment for mental health issues and alcohol abuse – remain as significant today as they were fifteen years ago.

Beyond this, the overview of studies revealed some less well-known risk factors, including:

- Suffering from a another mental disorder, especially a personality disorder or schizophrenia

- Having an eating disorder

- Being currently treated for a mental health issue

- Stressful or traumatic life events

- Sexual abuse

- Being bullied (including cyber bullying)

- A tendency to impulsive behaviour

- Poor problem-solving abilities

- Feelings of hopelessness

- Financial problems

- Difficulties or setbacks at work or school

- Problematic family relationships

- Troubled social relationships or troubled romantic relationships

The addition of sexual abuse to the list deserves special attention and further study, given that an often-cited and study of 2008 found no relationship between the two.

Today, some sources claim that up to half of people who engage in self-harm have been sexually abused.

Physical Illness as a Cause for Self-Harming

While suffering from a mental disorder has been well-studied as a risk factor for self-harm, only recently has physical illness been taken into consideration. A study published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 2014 found that certain illnesses did indeed put people at increased risk for self-harm.

These conditions, ranked from most likely to least likely, included epilepsy, asthma, migraine, diabetes, skin disorders like psoriasis and eczema, and rheumatoid arthritis. Diseases associated with little to no risk included cancer, congenital heart disease, ulcerative colitis, and sickle cell anemia.

The link between certain illnesses and self-harm suggests that help with issues like pain management and body image may decrease the risk of self-harm for some people.

The Role of the Internet in the Rise of Self-Harm

Tallulah Wilson’s tragic death brought new focus to the role played by the internet, which Wilson’s mother referred to a “toxic digital world” that parents are powerless to shield their children from.

Sites that might have claimed to help harmers find mutual support were accused of encouraging high-risk teens to continue the behaviour rather than seek professional help.

To an extent, pictures and story-sharing do romanticise and legitimise self-harm. And the activity of taking pictures of one’s own injuries and looking at pictures posted by others can fill an empty spot in a teen’s life, or make them feel part of something.

Tallulah Wilson was an example of how exposure to pictures and thoughts of self-harm and suicide can play into a teen’s desire for group acceptance. Wilson’s mother described her daughter as a heavy user of such sites to the point of addiction, and recounted how her daughter had become obsessed with the recent suicide of another girl at her school.

But are these connections being made between internet self-harm sites and the rise in self-harm speculation, or evidence-based? Increasingly the latter.

A U.S. study of 1560 internet users age 10 to 17, published in the Journal of Adolescence in December, 2014, found that 1% of the group had visited web-sites that encouraged self-harm. Those who had visited were 11 times more likely to more likely to think about hurting themselves and 5% more likely to have suicidal thoughts. These alarming findings prompted the study’s authors to recommended evaluating internet usage as part of assessment interviews with troubled teens.

Why the Rise of Self-Harm Really Matters

A decade ago, this connection between self-harm and suicide was not established. Some even suggested that it was a non-fatal alternative to suicide. But new evidence shows just how serious the link is.

As the case of Tallulah sadly demonstrates, while self-harmers rarely begin with the intent to kill themselves, in the long run self-harm can be a step in the direction of suicide.

The Bristol study mentioned earlier found that within a year of a self-harm incident, 3 in 200 people will kill themselves. Within five to ten years, that number rises to 1 in 25.

And it’s young men who are most at risk. Although girls are more likely to self-harm, boys are less likely to seek help and more likely to commit suicide.

(If you are worried someone you love is considering suicide, please read our useful article on How to Help Someone Who Is Suicidal).

Why Can’t More Be Done?

The welter of new research around issues of self-harming is helpful, but mental health professionals are still struggling to reverse the epidemic.

One problem is that patients often don’t get professional help until the pattern is entrenched, has serious consequences, or because they are referred for treatment of another problem.

Teens who practice self-harm often end up in therapy at their parents’ insistence, and may prove secretive, uncooperative and reticent patients, unwilling to disclose incidents of self-harm or underlying issues. A good deal of the therapist’s time may be spent in gaining the patient’s cooperation and trust, and simply keeping them in therapy.

These difficulties make the role of those in direct contact with the self-harming person crucially important. Parents, teachers, school counsellors, A&E doctors, and even peers can all help identify the sufferer before the urge to self-harm becomes a habitual, long-standing pattern.

As studies have repeatedly shown, early intervention and treatment will make therapies, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to help the person reframe thoughts and modify behaviour, more likely to succeed.

Do you have a comment to make on the rise in self-harm or a personal experience you’d like to share? Do so below.