What is Compassion-Focused Therapy?

Looking for a therapy that raises your self-esteem and helps your relationships? Compassion-focussed therapy might be what you need.

Looking for a therapy that raises your self-esteem and helps your relationships? Compassion-focussed therapy might be what you need.

What is compassion-focused therapy?

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT) is a kind of psychotherapy designed to help those who suffer from high levels of self-criticism and shame. It helps you to learn how to feel kinder towards yourself and others, and to feel safe and capable in a world that can seem overwhelming.

Founded by British clinical psychologist Paul Raymond Gilbert, CFT is an integrative approach that uses research and tools not just from psychology, but also from evolutionary theory, neuroscience, and Buddhism.

How is CFT different to other talk therapies?

It’s true that all talk therapies involve compassion, and that the very nature of therapy is that that you learn to be nicer to yourself. All psychotherapists work to show you understanding and empathy.

It’s also true that compassion-focused therapy utilises tools and techniques that other forms of therapy do, such as monitoring your thoughts and feelings and looking at your past.

But compassion-focused therapy puts a greater focus than other therapies on developing your ability to feel and act compassionately and kindly, towards yourself and others.

How compassion-focused therapy was created

To understand how compassion-focused therapy is different, it can help to look at what inspired its development in the first place. Founder Paul Raymond Gilbert worked with clients with complex mental health challenges who often had backgrounds that involved neglect, abuse, and trauma. He noticed many of these clients suffered a very high level of shame and self-criticism that didn’t improve with cognitive therapy only. In other words, therapies that helped Gilbert’s clients understand their negative thoughts and behaviours didn’t make them actually feel better.

Gilbert began to realise that his clients needed emotional resources as well. They needed tools to be able to soothe themselves and experience inner peace .

Gilbert began to realise that his clients needed emotional resources as well. They needed tools to be able to soothe themselves and experience inner peace .

So CFT was developed to help create positive emotional responses that other therapies didn’t in those who suffered with a low sense of worth.

Compassion-focused therapy doesn’t have to be used by itself, and is often used alongside other types of therapy. For example, a cognitive behavioural therapist or a person-centred counsellor might also integrate Compassion-focussed therapy into their work with clients.

What issues can CFT help with?

Compassion-focused therapy helps anyone who struggles with the following issues:

- deep feelings of shame

- an unrelenting inner critic

- a history of emotional or physical abuse including neglect and bullying

- an inability to feel kind towards themselves

- difficulty believing the world is a safe place

- anxiety and possibly panic attacks due to feeling life is threatening

- find it hard to trust others.

Compassion-focused therapy may help with the following mental health challenges:

- self-esteem issues

- severe and chronic depression

- anxiety and/or panic attacks

- eating disorders.

The evolutionary psychology behind CFT

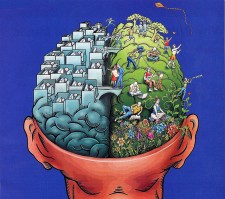

Compassion-focussed therapy looks at the way we have more than one ‘brain’.

Compassion-focussed therapy looks at the way we have more than one ‘brain’.

The ‘old’ brain, which we share with all animals, helps us take care of our needs. These includes not only food and shelter and a desire to be loved, but also our personal safety. We all have an inbuilt defence system that causes our ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ reaction. The ‘old’ brain gives all animals basic emotions like anxiety, anger, neediness, and sadness.

But somewhere along the line, as humans we then also developed a ‘new’ brain that allows us to have a distinct sense of self, and to visualise and imagine. We can choose how we want to feel and how we want to live, and come up with ideas we then make happen. These are all things other animals cannot do.

The problem with our ‘new’ brains is that they they can get mixed up with the ‘old’ brain in ways that cause us problems. The basic emotions and drives of the old brain can take over the new brain, using it’s creative force to stir up primal and protective emotions.

For example, imagine you bump into an ex who is with a new partner and seems very happy. Instead of seeing it as an opportunity to visualise your own future in a partnership that makes you happy, you might be filled with anxiety and anger and start thinking of ways you can punish your ex for not being so happy when with you. You might even start writing an angry letter in your head. Your old brain, feeling threatened, starts using your new brain to do its work.

Why does this evolutionary theory matter?

The positive side is that when we understand the whys and hows of our brain’s behaviour, we can learn to notice and change the way we think. Therapies like Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as well as Mindfulness-based therapies focus on just this sort of thought recognition and re-focusing.

What Compassion-focussed therapy also brings into the picture is two things. The first is to let go of self blame for having such negative thoughts. Nobody chooses to have a brain that creates angst. But our brains evolved to be reactionary, it’s simply the way they are designed.

The second idea that we can also then choose not just to generate new thought patterns, but also to generate certain emotions that can help us, such as compassion. As well as protective emotions like anger and anxiety, the brain is also designed to create kindness and understanding.

If we focus on activating this compassionate part of our brain we can actually teach our mind to react in new ways. In CFT, this is called “Compassionate Mind Training”.

But is compassion really that effective?

The idea of generating compassion to alleviate distress is actually a basic precept of ancient Buddhism that has been around for over two and a half centuries. And compassion has long been recognised as an integral part of the client-therapist relationship in psychotherapy.

The idea of generating compassion to alleviate distress is actually a basic precept of ancient Buddhism that has been around for over two and a half centuries. And compassion has long been recognised as an integral part of the client-therapist relationship in psychotherapy.

But is it proven to work? Yes, by both psychological research and science. It has been found that by focussing on developing our compassion, we can create positive effects on both our brains and our immune systems. Parts of the brain are shown to light up when we are kind to ourselves or others, and studies of evolution show we are biologically designed to respond well to being cared for and treated kindly.

Research also shows that compassion is something you don’t have to have naturally, but can train yourself to be better at.

Compassion-based therapy and the three ‘affect systems’

With its focus on the evolution of the brain, one of the main theories of CFT is that there are interconnecting ‘systems’ that the brain operates on that that need to be managed if we want to be happy.

These systems determine our feelings and ways of relating to others and the world, such as if we feel happy and safe, and are called ‘affect systems’. The three such systems that CFT focuses on are the threat, drive, and contentment systems.

The ‘threat’ system

The threat system is protection focused. It quickly notices anything that is perceived as a threat and then reacts with feelings like anxiety or anger, emotions that trigger us to protect ourselves. This is the affect system responsible for the ‘fight, flight, or freeze/submission’ mode that evolutionary psychology likes to focus on.

The drive system

The ‘drive’ system is excitement focused. It motivates us to attain resources and rewards. This is not just food and a place to live, but also things such as passing a test and getting our license, or managing to get a date with someone we really like. Such things bring with them anticipation and pleasure. So this system is thus related to feelings of arousal, stimulation, and energetic highs.

The ‘drive’ system is excitement focused. It motivates us to attain resources and rewards. This is not just food and a place to live, but also things such as passing a test and getting our license, or managing to get a date with someone we really like. Such things bring with them anticipation and pleasure. So this system is thus related to feelings of arousal, stimulation, and energetic highs.

The ‘contentment’ system

This system is soothing focused. It triggers when there is no threat, or nothing that needs to be achieved. It causes us to feel peaceful, calm, and happy, which also leads to us feeling safe and socially connected.

How the systems interact

Compassion-focused therapy believes that these three systems can get out of kilter, and the focus is to get them back into balance. The focus is on developing then using the contentment and soothing system to regulate the other two systems.

It’s been found that in people with high levels of shame and self-criticism the threat and/or drive systems are often working too hard. And the contentment/soothing system is under-active or somehow not accessible to the other drives.

One of the reasons the contentment system can be underdeveloped is if we don’t learn soothing as a child. This could be due to, for example, a parent who didn’t show us soothing caring behaviour when we were an infant. The idea that a child needs to be able to safely connect to a parental figure as an infant is the basis of attachment theory, which CFT integrates.

It’s also common to have an overdeveloped threat system. As we grow up our brain develops ways to pick up and respond to what it sees as threats and helps us protect ourselves. For example, if we have a controlling or even aggressive parent, we’ll become submissive so as not to cause trouble.

This is called a ‘protective or safety behaviour or strategy’. The trouble comes when as an adult this reaction is still programmed into us, and our threat system stays on high, triggering us to still use the same strategy. While it might be a strategy or behaviour that served us when a child, as an adult it could be stopping us from learning and growing or from accessing our ability to self-soothe.

What Is Involved in CFT sessions?

A CFT therapist is committed to being an example of the attributes of compassion. These include sensitivity, sympathy, non-judgement, empathy, well-being, self-care, and distress tolerance.

A CFT therapist is committed to being an example of the attributes of compassion. These include sensitivity, sympathy, non-judgement, empathy, well-being, self-care, and distress tolerance.

So a CFT therapist creates an environment that is safe, kind, and accepting.

Then they work to help you learn the skills of compassion. The skills of compassion are designed to help you feel warm, kind, and supportive to yourself and others.

There is no one ‘set’ way a CFT session must go. Instead, there are a large range of tools and techniques your therapist might draw from. They involve harnessing your attention, reasoning skills, feelings, and behaviours to make compassionate choices.

For example, ‘compassionate attention’ can involve choosing to go through our memories and focus on the times we were good to others and they were good to us. Or it can mean learning how to focus our attention on the good in people.

‘Compassionate behaviour’ can involve learning to spot and reduce the things we do to keep ourselves ‘safe’. And it can mean learning to try things that might require courage but lead us towards our life goals. So you might, say, start to look at the way you choose to hang around people who you’ve known a long time but aren’t treated so well by, and try to push yourself to meeting people you are more accepted by. Or you might be asked to try ‘compassionate imagery’, such as visualising compassion flowing out from you to others.

Of course what is important is that you don’t push yourself too hard to learn these skills, effectively bullying yourself. As the whole idea is to learn to be gentle with yourself. But your therapist will help you notice if you are falling into this old habit.

Useful References

- Introducing Compassion-Focused Therapy by Paul Gilbert

- Training Our Minds In, With, and For Compassion by Paul Gilbert et. al.

Do you like the sounds of Compassion-based therapy, but still have a question about it? Ask below, or share your thoughts.

Photos by Kate Ter Haar, Roger H. Goun, Allan Ajifo, Hartwig HKD, Tambako the Jaguar, and Wonderlane

Where/how can I find a CFT therapist in London?

I’m afraid we don’t currently have any one on our team who offers it, although we have psychotherapists who practice Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Do you offer training in compassion focused therapy for mental health professionals?

Unfortunately we are not a training institution, we are an organisation that connects those seeking therapy with therapist and disseminates information to fight the stigmas against seeking help.

I am suffering from trauma from being a spiritual group which used Buddhist and Hindu ideas. Is this kind of therapy appropriate for me, or could it just be triggering?

It’s a very good question. It would probably very much depend on the therapist and about what works for you. So ask yourself some good questions. For example, what about the spiritual group attracted you? Are the things that attracted you different than the group itself? Can you separate those out from the group or is it all too connected? What drew to find this article? What are your values? What values would you hope a therapist to have? The other thing is that it’s also about the therapist him or herself, and how you ‘click’. Finding a therapist is a bit like dating, it can take some first appointments to find the one that is right for you. So don’t be afraid to book an appointment and be very honest about what you are looking for and arrive ready to ask good questions. You are not obligated to continue if you try a few sessions and it’s not right for you. You are the client, after all. Otherwise, you might find our articles on finding a therapist helpful….

Hi there.

I am a trainee psychotherapist – Person -Centered . I am writing a reflective report about CFT and would like to know more about research which support the CFT. Could you let me know where I can look?

Thank you very much.

Alena

Hi Alena, I’m afraid we cannot help. We are an online portal for articles on psychology and therapy, but we don’t do research for students (but it’s amazing how many ask). We’d suggest you use Google search and the well known portals that hold all research papers. While some do involve paying they might have student rates. Best of luck.