Kids Who Won’t Leave Home? The Effects of Helicopter Parenting

It used to be a given that your child would eventually grow up and leave home.

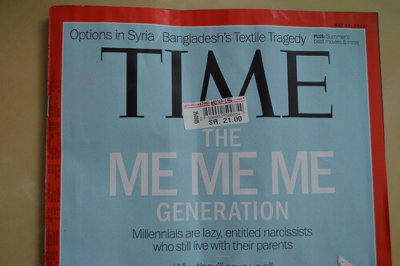

Not so much nowadays. The latest generation of ‘millenials’ see parents dealing with their children wanting to live at home even after university, or handling ‘boomerang kids’ who move out but rush back the second life gets too hard.

How did we end up with a generation who don’t want to be independent?

Several social observers, including author Melanie Phillips and journalist Po Bronson, trace today’s problems back to the 1960s. This was when concepts like self-esteem, popularised by Nathaniel Branden in his book, The Psychology of Self-Esteem, moved into the mainstream.

Branden believed that healthy self-esteem was the key to happiness and success, promising fulfilment through effort, achievement, and self-responsibility. Within a few short years, the original idea became hopelessly distorted. Self-esteem became a goal in itself, detached from effort, action, and results. It didn’t much matter what you did or didn’t do, as long as you felt good about yourself.

Between 1970 and 2000, over 15,000 scholarly articles were written on the importance of self-esteem and its impact of almost every facet of life. But in 2003 a stringent review of the studies found only a handful – some 200 – met professional research standards. Worse, they did not show evidence that supported the movement at all. Having high self-esteem did not correlate with higher grades or career success, nor did it reduce substance abuse or criminal behaviour. In fact criminals were found to have inflated self-esteem.

By this time, of course, the self-esteem movement had been inculcated by the larger culture, and had become the default approach to education as well as culture.

Education became about certificates of ‘participation’, and wrong answers accepted as long as the child had done his or her “best.”

This over focus on self-esteem affected parenting in the form of caring parents lavishly praising their children for ordinary achievements, continuously telling them how smart they are, and trailing them like detectives, ready to jump in and avert any slight, frustration, disappointment, or ego-blow that might come their way.

Helicopter parenting – are you guilty?

This new and particular approach to child-rearing quickly made a name for itself, casually referred to as “helicopter parenting” and known among professionals as “over-parenting”. By either name, it refers to parental over-involvement in children’s lives, and a parenting style found on the belief that, with all obstacles removed, children will flourish into their full potential.

Except that too often the message gets garbled.

Parents who make all the child’s decisions, schedule every minute of free time, and perform tasks the child could perform for himself can convey the message, “You’re not competent to do these things for yourself.” Children buffered from disappointment and failure miss opportunities to develop emotional resilience, while over-protected children fail to develop self-protective skills and become targets for bullies.

And children whose talents and intelligence are continually over-praised show reluctance to take on anything challenging, either for fear of falling short or because they become frustrated and opt out when success doesn’t come easily. When everyone gets a trophy, effort and real achievement are as valueless as the trophy itself.

The Kids Aren’t All Right

It’s easy to dismiss today’s nest-clinging fledglings as pampered middle-class elites who feel entitled to coast through life on the fruits of their parents or fellow citizens’ labor.

In fact, the psychologists whose offices they often turn up in paint a quite a different picture.

Beneath the façade of ease, many of these allegedly ‘privileged and spoiled’ kids are anything but calm. They are less engaged in school than their peers, more likely to have social adjustment difficulties, and suffer higher than normal levels of depression and anxiety.

By: istolethetv

Far from becoming confident, independent adults, they are fragile, easily wounded and over-dependent on the opinions of others. When turned loose on the world, their expectations are often so wildly unrealistic they become bewildered and return to the nest, fearful of venturing out again.

But is it really over-parenting that is to blame?

Research backs up the fact that over-parenting has negative psychological effects. A 2012 study funded by America’s National institute of Mental health found that “higher levels of parental anxiety, rejection, and over-control were related to higher levels of social anxiety” in the youth taking part.

And a recent 2015 study headed by Brigham Young University that looked at over 400 university students connected helicopter parenting to low self-esteem and risk-taking behaviours.

The Brigham study then went one step further, going against previous conclusions that helicopter parenting was done out of sheer good intentions, stating that it is ” becoming increasingly clear that helicopter parenting (a) in and of itself is not inherently warm, (b) is not facilitative of emerging adults’ development, and (c) represents another form of control (besides behavioural and psychological control)”.

Put like that it’s hard not to imagine, if you are a chronic over-parenter, that you wouldn’t feel a little condemned.

It’s important to remember that few people consciously decide to control their kids. More often, any need to find control through family dynamics is itself a result of your own unresolved and unconscious issues over any bad intent.

What do I do if I can’t stop myself from helicopter parenting?

First of all, don’t panic. Things can change, and quickly with the right support. Self-help is a great start, and there are numerous books and online information sources around parenting your child in a way that encourages, rather than diminishes, his or her independence.

Then don’t overlook the value of seeking support. A counsellor or psychotherapist can help you get to the root of why you feel so in need of monitoring and over-supporting your child. Family therapy is another option, helping the dynamic of your family unit improve and leaving all of you better able to communicate with each other and more able have your needs met.

Interested in 12 tips for parenting in a way that sees your child develop independence? Sign up now to receive an update when we publish the next piece in this series.

Have something you want to share about helicopter parenting? Do so below, we love hearing from you.