Self-Harm: A Help Guide

How is self-harm defined?

Self-harm is the intentional and direct injuring of oneself as a coping strategy when faced with overwhelming emotional states or situations. It includes behaviours like cutting, scratching, picking and burning of the skin, and banging or hitting body parts. It can include less apparent harm as well, like substance abuse, poisoning with prescription and non-prescription drugs, overeating or undereating, asphyxiation, and wilfully putting yourself in dangerous situations.

Self-harm is sometimes called deliberate self-harm (DSH). Self-injury or self-mutilation are also used when referring to deliberate acts like cutting and burning.

Why would someone self-harm?

While it might seem as if someone who self-harms is looking to commit suicide, this isn't often the case. Self-harm is more often than not a coping mechanism that allows someone to want to live, giving them a sense of control and/or a moment of release when things seems too much. For some, the pain of self-harm works to displace emotional pain and unwanted thoughts. For others, who feel numb from emotional pain, the physical pain of self-harm is used as a sort of affirmation they exist, and still others report they use self-harm as a way to punish themselves.

Self harm can be triggered for by the following:

Trying to cope with difficult situations

This can include money troubles, issues at school or work, relationship breakdown, being the subject of bullying, sexual identity issues, and any other challenging experience that feels overwhelming.

Trying to cope with negative feelings

These feelings can include anger, loneliness, sadness, frustration, guilt, anxiety, stress, powerlessness, distress, emptiness, numbness, disgust, a sense of failure, abandonment, perfectionism, and having very low self-esteem.

Trying to escape unwanted memories

These can be old memories, such as of childhood abuse or abandonment, or recent memories, such as a breakup, criminal attack, or any other experience that has left someone feeling upset, a failure, and/or ashamed.

Trying to gain control over one's life and/or body

If life is severely out of control self-harm can seem like a way to be able to take charge of something. And if someone has experienced physical or sexual abuse, or been neglected or severely bullied, they can be left feeling they have limited control over their body and turn to self-harm as a way of regaining ownership.

Trying to communicate that help is needed

When someone does not find it easy to use conventional forms of communicating feelings, they may choose to harm themselves as a way to call out for attention and help.

Self-harm is also a symptom of other mental disorders

Read more in the section below 'Related Psychological Conditions for Self-Harm '.

How common is self-harm?

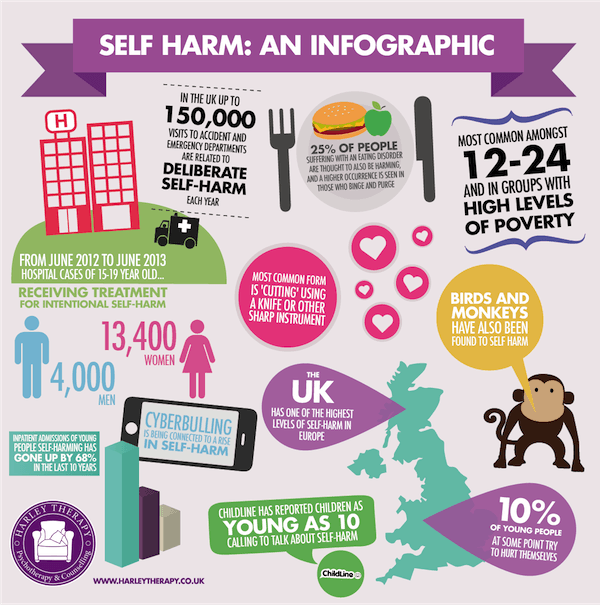

Self harm is much more common then assumed or even reported. It can affect people of any background and of all ages, although it is most prevelant amongst adolescents aged 12-24 and groups with high levels of poverty.

The UK has one of the highest levels of self-harm in Europe with at least 10 per cent of young people thought to at some point try to hurt themselves, and up to 150,000 visits to accident and emergency departments being related to deliberate self-harm each year. These figures might even be low due to the secretive nature of the condition meaning many self-harmers do not come forward for help.

While for most people a problem with self harm tends to resolve before adulthood, it is thought that 10 per cent continue to harm into their adult lives.

The most common form of self harm is 'cutting', using a knife or other sharp instrument to break the surface of the skin. Females are seen as more likely to self-harm then males, but this might be related to their tendancy to cut while boys can choose to punch walls, which isn't always recognised as the self-harm it is.

What are the usual signs of self-harm?

The signs of self-harm will often be visible wounds such as cuts, scars, or burns, or other unexplained injuries. But many people who self-harm choose to hide such evidence with clothing or jewelry, so sometimes a telltale sign is someone keeping themeslves covered at all times, including in very hot weather. Of course other sorts of self-harm, like substance bingeing, leave no visible marks.

Self-harm is a result of a precarious state of mind, so other signs can include depression, mood swings, loneliness, frustration, guilt, anxiety, powerlessness, distress, and very low self-esteem.

The stigma

There are still many misconceptions as to why people self-harm. It is obviously a difficult thing for someone who is not driven to abuse themselves to understand, going against natural instincts of self-care as it does, and seemingly so counterproductive.

This leads to the misconception that ‘people harm to seek attention’. While some do harm as a cry for help, most self-harmers hide their behaviour and don't want others to know. Self-harm is often about feeling a sense of control when the world feel out of control, and privacy allows this sense of being in charge.

There is also the misguided idea that those who self-harm must be very unwell. Self-harm itself is not a condition but a behaviour. While some who self-harm will be diagnosed with a personality disorder, for many self-harm is just a sign of psychological challenges.

Another misconception is that those who self-harm are trying to commit suicide. Self-harm is often instead a coping mechanism that many state helps them want to live, by giving them a way to feel they can manage when life is difficult and bringing a sense of relief, however misguided.

It is true, however, that many people who commit suicide self-harmed in the past. Self-harm usually exists alongside depression. It's said that those who have self-harmed are 100 times more likely than the average person to die by suicide in the following year.

Psychological conditions associated to self-harm

Self-harm is connected to depression and anxiety.But if you are self-harming and don't fit the category of general depression, it's possible that your habit of self-harm is a symptom of a bigger psychological disorder. This can include borderline personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and even schizophrenia.

Eating disorders are common bedfellows of self-harm, with both conditions seen mostly in adolescents and females and related to depression and a need for control. A huge 25 per cent of people suffering with an eating disorder are thought to also be harming, and a higher occurrence is seen in those who binge and purge than those who starve themselves.

Self-harm has also been connected to autism. It is now thought that between 20-30 per cent of people with autism will self-harm in some way. But really there is a difference to be found as many autistic harming behaviours, like head banging, scratching at skin, and punching things, can be done as a form of stimulation without obvious intent.

Alcoholism is linked to self-harm. One half of people who arrive in accident and emergency rooms after deliberate harm have been found to have consumed alcohol, and it's thought that 10 per cent are alcohol dependent.

How do you get a diagnosis of self-harm?

A diagnosis will be made by a health professional such as your GP, a counsellor or psychotherapist, or a doctor at accident and emergency. The process will consist of possible physical examination and a series of questions asked by the mental health professional.

If you are curious as to how these questions are chosen, most healthcare providers in the UK refer to guidelines set forth by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). You can find out more about what NICE recommends around issues of self-harm here.

It's of course much better to find the desire to reach out and receive help and a diagnosis then end up in an accident and emergency room because of your self-harming. You can talk to a mental health professional such as a counsellor or psychotherapist, or to your GP. If you are a young person you can get a referral for help from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) from your GP or also from a school nurse, a teacher, a learning mentor or a family worker.

If you do want help but are nervous about going for a diagnosis, you might find reaching out to others on self-harm forums or calling a self-harm hotline can be a good first step. See the resources section below to get you started.

Recommended treatment for self-harm

While self-harm is connected to other mental disorders that may benefit from drug treatment, drugs are not a recommended intervention to reduce self-harm itself. Instead, psychological help and support is the best step to recovery from self-harm.

It's important to remember that stopping the self-harm itself is only part of the healing journey. Once the harming is stopped the issues the harming was acting as a coping mechanism for can surface, which is why the help of a mental health professional or support group is highly recommended as part of treatment.

The aims of treatment will vary for each individual. Some examples may be to reduce the number of self-harm incidents, improve well-being, reduce risk, improve social functioning, reduce negative emotions such as depression and anxiety, and to enhance self-esteem.

Talking treatments are proven effective for self-harm.

Psychodynamic therapy is very useful at helping individuals explore how their past experiences have determined their current life choices and emotions, and how they can make different choices for their present and future.

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is also recommended for treating self-harm. A short term therapy, it helps you to notice the relation between your thoughts, feelings, and actions, and gives you practical tools to start to manage them better.

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) is highly recommended for self-harm, especially if it is a symptom of borderline personality disorder which involves intense and sudden surges of emotion that can feel unmanageable. DBT helps you moderate your emotions and distress, make practical choices for yourself, and become more aware of your feelings and choices moment by moment. (You can read an academic paper with an interesting case study about just how affective DBT is for self-harm here.)

Talking therapy can be done one-on-one, and sometimes with self-harm family therapy is also helpful.

Other approaches used in the treatment of self-harm and associated conditions include teaching emotion regulation, distress tolerance, mindfulness, risk management, occupational therapy, cognitive analytic therapy, transference-focused psychotherapy, and mentalisation-based therapy.

Group therapy or support groups can be very helpful when it comes to self-harm, and help you feel understood, realise that you are not alone, and see that what you are doing is not something to be ashamed of but just something to get help over.

Self-help can be an effective part of treatment for self-harm. Using books, forums, and online resources self-harmers can learn to recognise their patterns and triggers, distract themselves with more healthy choices, build self-esteem and look after themselves better.

What is the risk if self-harm is not addressed?

Self-harm is a sign of emotional difficulty and depression. Left untreated, depression can increase and lead to suicide attempts. Depression is also now connected to a lower immune system which can lead to medical illnesses.

Self-harm also has many physical side effects. If help is not sought problems from self-injury can include tissue damage, permanent scarring, injury to a vein or artery, and infection. Other self-harm behaviours such as substance abuse and overdosing can lead to risks in circulatory system disease, blood poisoning and digestive system disease.

The risk of death grows if if the behaviour continues without treatment, with the risk of suicide in the future increasing.

What if treatment is received?

The longer self-harm goes on, the longer and more difficult the journey back to a healthy life, but it is possible to achieve a total recovery.

The risk of all negative physical health implications are reduced once treated.

When the self- harming habit stops the emotional issues that the self-harm was keeping at bay will need to be faced. But many individuals who seek treatment learn to cope with their feelings and pain in a more productive way and have found that after treatment they lead healthy, positive lives free from self-harm.

Well-known individuals thought to have self-harmed

Self-harm can affect anyone, regardless of background. For example, well-known individuals who have been known to self-harm include Princess Diana, Russell Brand, Tulisa Contostavlos, Johnny Depp, and Angelina Jolie.

Tips if you are tempted to self-harm

- Mark instead of harm using a red felt tip pen where you might usually cut

- Hit pillows or cushions, or have a good scream into a pillow or cushion

- Rub ice across your skin where you might usually cut

- Get outdoors and have a fast walk

- Exercise in any format to release adrenaline and change your mood for the better

- Make lots of noise, either with a musical instrument or just banging on pots and pans

- Write negative feelings on a piece of paper and then rip it up

- Keepa journal that nobody else has to see

- Put elastic bands on wrists, arms or legs and flick them for a moment of pain instead of real harm

- Call and talk to a friend (not necessarily about self-harm)

- Engage in something creative

- Get online and looking at self-help websites

- Call a helpline

Resources for dealing with self-harm

The Scarred Soul: Understanding and Ending Self-Inflicted Violence. Alderman.

Healing the Hurt Within: Understand and Relieve the Suffering Behind Self-Destructive Behaviour. J. Sutton.

A Bright Red Scream: Self-Mutilation and the Language of Pain. Marilee Strong.

Useful Websites

- www.selfharm.co.uk

- www.youthnet.org

- www.lifesigns.org.uk

- www.childline.org.uk

- www.samaritans.org.uk

- www.nshn.co.uk

- www.befrienders.org

Useful Telephone Numbers

- Samaritans – 08457 90 90 90

- ChildLine – 0800 1111

- Family Lives (formerly Parentline Plus) – 0808 800 2222

- NSPCC – 0808 800 5000

Counselling and Therapeutic Services and Organisations

There are many trained professionals who will be able to support you such as counsellors, psychotherapists, psychologists and psychiatrists.

When seeing a healthcare professional you will normally have an initial assessment. This will include some questions to identify the issues, causes and problems. Try to be honest and open in your answers. The person asking the questions is there to understand and help.

Counselling and psychotherapy clinics - search through online directories for one in your area. Harley Therapy is one such private practice in London, UK that can assist with self-harm treatment. Most workplace insurances now cover visits to a therapist, enquire with human resources at your organisation.

The NHS - an alternate to a private practice in the UK is seeing your GP and asking for a referral to a specialist.

Mental Health Charities - organisations such as MIND, Rethink, Young Minds, Mental Health Foundation and National Self Harm Network may provide support groups, therapy and advice in your local area. You might want to call your local council to enquire about such organisations in your area.

If you can identify with the issues above, please remember - you are not alone. It takes great courage to seek help, but we very much hope you will find a suitable avenue to follow.

References

Alderman, T. (1997) The Scarred Soul: Understanding and Ending Self-inflicted Violence. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Bergen, H., Hawton, K., Waters, K., Ness, J., Cooper, J., Steeg, S., Kapur, N. (2012). Premature death after self-harm: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet. 3, 380.

Boyce, P., Oakley-Browne & Hatcher. (2001). The problem of deliberate self-harm. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. Vol 14 (2) 107-111.

Claveirole, Anne; Martin Gaughan (2011). Understanding Children and Young People's Mental Health. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Fox, C., Hawton, K. (2004). Deliberate Self-Harm in Adolescence. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Hawton, K., Townsend, E., Arensman, E., et al (2003). Psychosocial and pharmacologial treatments for deliberate self-harm. Cochrane Methodology Review. (Cochrane Library, John Wiley) Issue 3.

Hollander, Nock & Teper (2007). Psychological Treatment of Self-Injury Among Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session. Vol. 63 (11), 1081–1089.

Kettlewell, C. (2000). Skin Game. New York: St. Martin's Griffin.

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review 27(2): 226–239.

Klonsky, E. D., Oltmanns, T. F., and Turkheimer, E. (2003). Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 160(8): 501–1508.

Laye-Gindhu, A., Schonert-Reichl, Kimberly A. (2005). "Nonsuicidal Self-Harm Among Community Adolescents: Understanding the "Whats" and "Whys" of Self-Harm", Journal of Youth and Adolescence 34 (5): 447–457.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2004). National Clinical Practice Guideline 16: Self-Harm. The British Psychological Society.

Putnam F., & Trickett, P. (1997). Psychobiological Effects of Sexual Abuse. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. (Psychobiology of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder) 821, 150-159.

Sutton, J. (1999). Healing the Hurt Within: Understand and Relieve the Suffering Behind Self-destructive Behaviour. Oxford: Pathways.